The Mysterious Disappearance of an Author and Publisher

Bei Ling

Dr. Gui’s apartment complex in Pattaya, Thailand

October 2015, Apartment Building in Pattaya, Thailand

In Thailand’s Pattaya, a soft white, Baroque-style building towers over the nearby silver beaches. Outside the luxury apartment building, completed after years of construction, a golden Buddha stands in silence. This neighborhood, where all is protected under 24-hour security, seems peaceful and pure, like Shangri-la. Dr. Gui Minhai,[1] known as Ah-hai, kept residence on the seventeenth floor, facing south toward the Gulf of Thailand. Gazing out from its three seaward arching balconies, the view is unobstructed, with water extending as far as the eye can see. From time to time, this mysterious Chinese author and Hong Kong publisher would stay here for a spell, leaving the clamour of Hong Kong politics and business far behind him. Hiding here alone, he would spend his days writing and compiling books while remotely managing the Hong Kong publishing, distribution, and bookstore empire he gradually built over ten years. In recent years, his wife living in Germany or his daughter studying in England would occasionally visit. Once in awhile, he’d invite his employees or his old poet friends to holiday here.

As in the past, Dr. Gui on October 6 flew from Hong Kong to Bangkok, where he spent a four-day layover. On October 10, he returned to his seaside condominium in Pattaya. In the afternoon of October 17, Dr. Gui drove back from picking up groceries in a t-shirt and shorts. Outside the apartment building, he pulled his groceries out of the car and handed them to the security guard. After exchanging a few words, he got back in his car and drove away.

The panoramic view inside Dr. Gui’s apartment in Pattaya

November 2015, Hong Kong

In early November, two mutual friends of me and Dr. Gui from the United States and China informed me that Dr. Gui was missing. Attempts to contact him through email, skype, and phone returned no reply. This was unusual and alarming. There was evidence to corroborate these concerns–he hadn’t contacted the contractors renovating his apartment in Hong Kong to talk through the details of the renovation in more than 10 days. Moreover, on October 15, he said he’d be in Hong Kong at the end of the month to receive a friend visiting from Shanghai, but he never showed up.

On the evening of November 4, Wang Yiliang, an author friend living in Thailand forwarded me a short news story posted on Boxun, a Chinese news website based in the U.S., that read: “Hong Kong Publisher Gui Minhai (Dr. Gui) Suspected Kidnapped in Thailand.”

My heart pounding, I immediately sought out the source of this information. A Boxun reporter sent word that the information had been emailed anonymously, and that Dr. Gui was confirmed to be missing in Thailand.

It was already the middle of the night in Germany, but we could afford no delay in confirming this report with Dr. Gui’s family. I called his home in Düsseldorf, Germany, and his wife, a German citizen, answered. Most shocking to me was that she had no knowledge of what had transpired. In contrast to the alarming news I’d awoken her with, Dr. Gui’s wife stammered that it was not possible, it was simply not possible that he was missing, because “Ah-hai calls me regularly.” Even though her denial persisted, I could hear her voice trembling. I urged her to confirm the story with Dr. Gui as soon as possible.

The next day, afternoon in eastern America and evening in Germany, I called Dr. Gui’s wife yet again. She told me Dr. Gui had just called and emailed her, reporting he’s “safe and sound.” Dr. Gui told his wife it was not convenient to have contact with outsiders for now, as he had an urgent work matter to handle. I could tell by the tone of her voice that Dr. Gui’s reassurances had calmed her, but she seemed upset with both me and the media for “mistakenly spreading” the story of Dr. Gui’s disappearance in Thailand.

Thus, I believed the news report was made in error.

With this, I wrote the following note to Dr. Gui’s friend inquiring about his whereabouts:

“I just made another call. Dr. Gui’s wife said she just spoke with him, and that he’s perfectly fine! And thanks everyone. Please discard the police report. Thanks! xx

Sorry for the false alarm, everyone.

But, she said something really worrisome, so I may still bother you all yet.” (November 7)

But my trepidation was impossible to dismiss. I discussed the situation with Meng Liang,[2] a Hong Kong poet living in Taiwan and an old friend of Dr. Gui’s. He was sharp, pointing out similarities between Dr. Gui’s case and that of Yiu Mantin, his former publishing house colleague and chief editor of Hong Kong’s Morningbell Press. Back when Yiu was preparing to publish exiled writer Yu Jie’s new book “Godfather of China Xi Jinping,” he was jailed in Shenzhen in October 2013 for illicitly pilfering industrial chemicals across borders. A year later, Yiu was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment for “smuggling ordinary goods/items.” When Yiu was arrested, his family flatly refused to publish information about the situation, also reporting over and over again, “he’s fine.” During that time, Yiu’s wife might have been led to believe that privately seeking help from an intermediary in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference or the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Hong Kong was the best way to get Mr. Yiu back to Hong Kong. From beginning to end, this process was delayed three months. With a cool head I considered the comparison, and after analyzing it with friends became frightened— only under his loss of freedom did Dr. Gui report his “safety.”

Dr. Gui could not have foreseen that the software WeChat, designed in China but freely used across the globe, has long provided the means for tracking individuals’ personal information and whereabouts. Through his communication on this platform, Dr. Gui may have unknowingly revealed his address in Thailand, the duration of his visit, and information about his friends.

But, where exactly was Dr. Gui? Where was it that “he’s fine”?

A Jolting Loss for Hong Kong: Three Employees Arrested in China

How peculiar! The week of Dr. Gui’s disappearance, two employees of Mighty Current publishing company and the manager of Hong Kong Causeway Bay Bookstore all disappeared without a trace.

Causeway Bay Bookstore is sandwiched in Hong Kong’s most bustling neighborhoods. A well-known second story bookstore, its facade is not big, but it is a must-stop destination for mainland tourists scoping out Chinese politics books that can’t be published on the Mainland. Last year, Dr. Gui and his colleagues Lv Bo, Lee Po, and Mr. Lee’s wife acquired this bookstore, and Lin Rongji served as the store’s manager.

Lv Bo: Mighty Current general manager

Computer last accessed: October 14.

Date of disappearance: October 15?

Location: Shenzhen. Recuperating at his wife’s family’s home.

Reason for disappearance: Unknown.

Zhang Zhiping: Mighty Current business manager

Computer last accessed: October 22.

Date of disappearance: October 24.

Location: Dongguan city, Guangdong province. More than ten military police took him at gunpoint. After that, all contact was lost.

Reason for disappearance: Unknown.

Lin Rongji: Causeway Bay Bookstore manager

Computer last accessed: October 23.

Date of Disappearance: October 24.

Location: Shenzhen?

Reason for disappearance: Unknown.

These frightening cases of successive disappearances rocked Hong Kong society, but even more so shocked us friends of Dr. Gui.

Where are the missing four? Where is Dr. Gui?

This “mysterious force” appeared to “allow” Dr. Gui to mislead us and trust in his safety. At the same time, the particular demands of “respecting the family’s decision” made us hesitate.

On November 7, the day after Hong Kong’s Apple News reported his disappearance, Mr. Lin unexpectedly phoned his wife from Shenzhen, saying, “I’m quite safe, I’ll come back after a bit, please don’t fret.” After that, nothing.

That same day, I wrote an open letter on November 7 to PEN members expressing the hope that we would no longer be misled.[3]

“Thus, regarding the matter at hand, we must not blindly trust what the family says. I only need Ah-hai to appear just once, to tell us just one thing–where is he? Is he free, or not? No matter if it’s just one sentence, as long as he tells us where he is, that’s the only important thing.

In the early stages, we were led to believe he was safe, and so didn’t have the strength of conviction to ask for help or call for support. Perhaps we missed the best time to save him. I simply could not believe, that while his employees and associates were detained in Shenzhen, he was somehow alright…

Today, Hong Kong’s Apple Daily reported Causeway Bay Bookstore manager Lin Rongji called his wife after being detained in Shenzhen–further proof of my suspicions.

Thinking it over, there is no way I believe Ah-hai is ok, and now, I want to convince his wife that I have come to this conclusion after lengthy consideration. Everyone, please do not lower your guard…”

There were too many precedents for us to ignore. From that point onward, we could not blindly trust what the families of the disappeared told us. Our operation could no longer be postponed.

I’d go as far as to hypothesize that the motive behind the mysterious force under whose duress Dr. Gui had fallen, who detained the other three men, lay in amassing evidence of Dr. Gui’s so-called “crimes.”

Since Bangkok is a place to flee for Chinese applying for political asylum status with the United Nations, I wrote a letter on October 28 to friends in Thailand, warning them:

“Friends and PEN members in Thailand and Bangkok, please be aware… you must keep a low profile, limit the number of people you contact to three per day, and try not to share information on WeChat–by this you must abide, to avoid landing yourself in prison. Bear in mind, you are living under the rule of a post-coup militia government. If you stay in Thailand, your rights are not guaranteed and it will be easier to get arrested. Please, be vigilant!”

Rereading the letter, there was a sense of dark foreshadowing within.

An Important Breakthrough: The First Piece of the Puzzle

Aside from Dr. Gui, there were no other ethnic Chinese living in this seaside apartment building. While news of the disappearance of Dr. Gui–an ethnic Chinese and Swedish citizen–caused an uproar in the Chinese-speaking world and in the media, not a word about it could be heard in Pattaya. The apartment building’s property management office had long been utterly puzzled by Dr. Gui’s sudden disappearance and the four mysterious visitors who subsequently came to Dr. Gui’s apartment.

Three weeks had already passed since Dr. Gui’s disappearance. Not only had Thai police not yet opened an investigation, but his family hadn’t filed a report either. With no trail to follow, I and several friends of Dr. Gui formed a team to “break the case.” We anxiously searched for him, relying on one piece of information at a time, piecing together the puzzle. We made countless phone calls, analyzed the case day in and day out, approaching the case calmly and rationally. My team and I discussed the situation, making plans for every possible outcome. Finally, we decided to go directly to Dr. Gui’s apartment building in Pattaya to investigate.

On November 9, we made an important breakthrough in Dr. Gui’s case. Through a Chinese friend who cannot be named, Li Fang, a Chinese political refugee in Finland, ascertained the actual address of Dr. Gui’s apartment building. Subsequently, two ethnic Chinese friends in Thailand whose names cannot be divulged went to Dr. Gui’s residence in Pattaya, where they inquired about their friend’s whereabouts. Our ethnic Chinese friend spoke Thai fluently, and was able to communicate fluidly in Thai with Ms. Mai, the property manager, thereby gaining the confidence of the building’s management office. Within a month, the two were able to procure complete video and photographic records of all entry to and exit from the building.

That day, I promptly wrote to my team:

“They’ve already found Dr. Gui’s apartment in Pattaya, and are confirming the circumstances of his departure; local friends in Thailand are providing assistance. Thanks xx, keep it up.” (November 10).

Following the Clues

On October 17 at 1:15pm, a young male appeared to be standing guard in the shade of a bus stop outside Dr. Gui’s apartment building. After several minutes, Dr. Gui is depicted driving his own car, white with license plate number 5870, to the apartment building exterior. He then took the groceries he’d just bought out of his car, and asked the building security guard to take it to his apartment. Immediately after, he got back in his car and left with the unidentified man.

This was the last sighting of Dr. Gui before his disappearance. From that moment on, he has not returned.

Video screenshot from the garden outside Dr. Gui’s residential building: On the afternoon of October 17, Dr. Gui returned to the apartment building driving his own car after ordering take-out. Before going upstairs, he left immediately.

Screenshot from the apartment surveillance video: The man that Dr. Gui was seen leaving with on the afternoon of October 17.

Clearly, the mysterious force that took him had prior knowledge of his comings and goings. Perhaps he recognized this person, or maybe one of his so-called friends had introduced them?

This was not the only instance of interference; even more damning footage emerged.

In the afternoon on November 3, four mysterious men who appeared to have come from the casino underworld, with calm demeanors and sure in step, entered the promenade of Dr. Gui’s building. From analyzing and comparing the vocal movements of the four men in the video, it can be established that at least three of them spoke Mandarin Chinese. One man in red appeared to be the leader of this operation. Before entering the building, one man took a phone call. After they entered, Ms. Mai received a call from Dr. Gui. In English, Dr. Gui said the four men were his friends, and they could enter the building and stay the night at his apartment. After the call ended, the property manager asked the four men where Dr. Gui was. One man responded, Dr. Gui was gambling at a casino in Cambodia, and therefore wouldn’t be returning for awhile. After that, building security accompanied the four men in the elevator to the 17th floor, and opened his apartment to let them in. According to the building manager, before these four men left the apartment, they attempted to take Dr. Gui’s desktop computer with them, but the property manager refused. Grudgingly, the they left without it.

The panoramic view inside Dr. Gui’s apartment. His desktop computer is still there.

It can be deduced from the time stamp on the surveillance video that they only lingered in Dr. Gui’s apartment for around 20 minutes. Obviously, they hadn’t planned to stay longFrom this it can be determined, in my analysis, that within nearly half an hour, the men likely took his Swedish passport and copied all the files on his computer, including his bank account information and even his emails.

After Dr. Gui disappeared, on November 3, the four men who entered his apartment and attempted to take his computer.

Friends in Thailand also checked The visitor registry showed the men calling on Dr. Gui did not actually write in Thai, but rather used simplified Chinese to write a name: “He Wei” (何伟). Apparently, they are ethnically Chinese, sent there on a mission.

Screenshot of video footage from inside the apartment elevator: The four men who entered Dr. Gui’s apartment.

Screenshot of video footage from inside the apartment elevator: A man who entered Dr. Gui’s apartment. The man wearing red is the ringleader.

Dr. Gui called again! After screenshots of the four men who entered Dr. Gui’s apartment were published in news media reports, Ms. Mai once more received a call from Dr. Gui on November 6. Ms. Mai asked him, “Where in the world are you? Your friends have been looking everywhere for you.” In a nervous tone, without revealing where he was, he responded that everything was alright, adding: “I’m with friends doing computer [sic].” Before he could disclose his whereabouts, he hung up.

“I’m with friends doing computer.” Was this a hint?

We continued our search through every channel possible. From Ms. Mai’s cell phone, we know Dr. Gui’s three phone calls were made over the internet from numbers in Egypt, Poland, and the Congo, but it is beyond our authority to investigate from which country he actually called.

Since this event transpired, Dr. Gui’s family members have still not reported his disappearance to the Thai police. As such, I tried to convince Dr. Gui’s wife to call Thai police in Pattaya from her home in Germany to report his disappearance. As she failed to do so, my friend Li Fang asked whether he could use my name and a friend’s identity to get the property manager to report Dr. Gui’s disappearance to the Thai police. Doing so would prevent strangers from entering his apartment or even taking his computer. I agreed, and the report was filed.

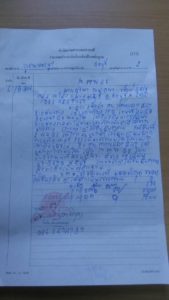

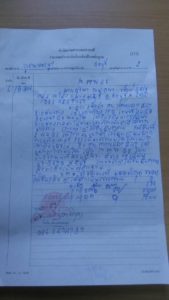

Police report form

Dr. Gui and his wife spoke on the phone every seven to ten days; with such frequent contact, the tone of his voice was not peculiar. Up until November 15, I was still in phone contact with Dr. Gui’s wife. She always told me, “He’s just fine!” The most recent time we spoke, I asked her directly: “Where is Dr. Gui at this moment?” “He’s in Thailand!” Because she held onto this conviction, I suggested to her at once: “When Dr. Gui calls next, please express that you’ll be flying to Thailand to see him in a couple days, and ask if he would fly to the Bangkok airport to meet you. This is the only way to test whether Dr. Gui is actually in Thailand, whether or not he is free.” She thought this course of action was reasonable, and thus approved of my suggestion.[4]

Several days later, Dr. Gui’s wife told a mutual German friend of ours that she had complied with my suggestion. She used WeChat to mention to Dr. Gui she’d be flying to Thailand to visit and asked him to go to the airport in Bangkok to meet her. Dr. Gui immediately responded, saying he would be unable to meet her and asking her not to fly to Thailand. As I saw it, this was tantamount to Dr. Gui covertly telling his wife that he was no longer free, or perhaps this suggested Dr. Gui had already been taken out of Thailand.

Where was Dr. Gui, after all? Still in Thailand, or already taken into custody back to another country? How exactly was he taken back to China?

I’m still searching.

Has Dr. Gui Really Already Been Returned to China?

On November 10, several foreign Chinese-language media outlets published a news story that caught my attention, a story that I couldn’t help but associate with Dr. Gui’s disappearance. The story was published in official Chinese media:

“On November 9, under the direction of the Ministry of Public Security, 282 police chartered four Chinese civil aviation planes to go abroad. They deported 254 individuals in Indonesia and Cambodia suspected of committing fraud back to China.”[5](Boxun news portal)

This news story aroused my suspicion:

1.“On November 9, under the direction of the Ministry of Public Security, 282 police” went in-person to Cambodia and Indonesia. As such, Chinese police officials must have arrived first in Indonesia and Cambodia to discuss the details of the operation. Is it possible they could have taken a detour to Thailand to conveniently handle other cases?

2.“…chartered four Chinese civil aviation planes to deport 254 individuals in Indonesia and Cambodia suspected of committing blackmail back to China.” This instance of cross-border cooperation with China, transferring the suspected criminals back to China, is between only the Cambodian and Indonesian governments, not the Thai government.

As Thailand and Cambodia share a border, I instinctively wondered: if Dr. Gui had already been kidnapped back to Cambodia, would he have been thrown in among the other 254 suspected criminals under similar charges and taken back to China?

With this, I phoned my friend in Bangkok who confirmed that it only takes around two hours to drive from Pattaya to Poipet, the casino town straddling the borders of Cambodia and Thailand. In fact, crossing the border into Cambodia is quite easy. Even without a passport, you can directly enter the border casino in Poipet through an acquaintance there. Once inside, you’re already in Cambodia. If you want to continue from the casino to do some sightseeing at the world-famous Angkor Wat, with its imposing architecture and meticulous reliefs, driving a car is also straightforward. With a passport, it’s more convenient. One need only have one’s passport stamped when exiting Thai customs and crossing the Cambodian border. For many years, guests traveling from Thailand to the Thai-Cambodia casino or to Cambodian tourist sites have used these channels to travel between the two countries. If one without a passport wants to go back to Thailand from Angkor Wat, the casino can arrange to take him.

For these reasons, it was technically feasible that Dr. Gui was escorted from Thailand to Cambodia and then detained in Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh with the group of suspected criminals for transfer back to China.

A Mobile Phone Left Behind in a Taxi

After the four mysterious men left Dr. Gui’s apartment building, they called a taxi outside the building’s gates and headed east toward Thai border town Poipet. While several of them haggled over the taxi fare, one man called the manager of Dr. Gui’s apartment building, asking him to turn off the air conditioning in Dr. Gui’s apartment as they’d forgotten to do so. Be it intentionally or unintentionally, the mobile phone used to call the building was unexpectedly left behind in the taxi. By browsing the phone’s call record, the driver was easily able to confirm that the last call was placed to Dr. Gui’s apartment building management office looking for lost property. Only then did Ms. Mai know that these four mysterious men were headed to the Thailand-Cambodia border town Poipet.

The exit strategy these four men took after leaving Dr. Gui’s apartment was not sufficiently professional. The recovered mobile phone not only divulged their direction, but even more so corroborates my own inferences.

Dr. Gui’s daughter, who goes to school in England, only learned of her father’s disappearance in Thailand on November 9–two weeks after he went missing–when Mr. Li, Dr. Gui’s associate at the Hong Kong publishing company, told her. After the disbelief and sorrow, she accepted interview requests from British and Swedish media, urgently connected with the Swedish government, and reported the case to the Swedish police, therefore making public her search for her father.

Two days later, media reported that she, who’d not heard word from her father for a long time, received a short English-language letter he’d written over Skype. Its contents were baffling and enigmatic, as Dr. Gui’s daughter neither requested money from nor lent money to her father recently:

“Hi, XXX, I have put in 30,000 HKD in your account in HK, and hope you be fine with everything [sic].” (November 11)

Without a doubt, the mysterious force that held control over Dr. Gui had sanctioned his writing this letter.

Five days later, Dr. Gui’s daughter received the $30,000 HKD on schedule through a Hong Kong bank. In the last month since Dr. Gui’s disappearance, this was the only time he had written and remitted funds to his daughter. In my view, the mysterious force allowed Dr. Gui to write and send money to his daughter because she had been calling for help searching for him in international media; this force wanted to convince her of his “safety” so she would not continue publicizing her search.

On November 12, a BBC reporter called Sweden’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs to inquire whether the Swedish government was aware of Dr. Gui’s disappearance from Thailand. The Ministry responded they had already learned of this news, and indicated the government was launching an investigation into Dr. Gui’s disappearance.

On November 17, one month after Dr. Gui’s disappearance, the International PEN Center[6] and the International Publishers Association jointly issued a statement of strong concern regarding the disappearance of this Chinese author and publisher.

On November 20, the Swedish police formally contacted Dr. Gui’s family to notify them they were dispatching police to Thailand to seek out the cooperation of Thai police in order to ascertain Dr. Gui’s whereabouts.

1984, Beijing

I’ve been an acquaintance of Dr. Gui’s for more than 30 years.

Our friendship can be traced back to Beijing in 1984, where this young poet was known by his pen name, “Ah-hai.”

On one Beijing afternoon in 1984, a certain chilliness had not yet dissipated from the early spring air. At Beijing Industrial University (now known as Beijing Institute of Technology), I had burrowed into my narrow, single-room, second floor apartment when someone–ignoring the doorbell–knocked on my door, asking in Beijing-speak with a hint of Ningbo accent, “Is Bei Ling there?” I opened the door to find a round-faced young man, cigarette smoke still idling in his mouth. This was how he serendipitously found me. He pulled out a mimeograph print of a long poem and introduced himself: “Ah-hai, student in the History Department at Peking University, composer of modern poetry.”

The Iron Curtain had already been lifted by that time, but authoritarian control was still severe. During this period, the ban on books was lifted, and “rebellious” Western literature and ideology bubbled forth like floodwater. At the time, literature became in vogue and poetry writing experienced a renaissance. Poetry served as a kind of business card for young literary types, who produced poems as a job applicant produces a resume. In those days, homes rarely had telephones, so to meet someone one would have to devise a way to seek out his address and go directly to his front door. If the person was there, you’d meet him; if not, you’d leave a note and try again another day. I don’t know how many doors Dr. Gui knocked on. In terms of poetry writing, contacts in underground poetry circles, and connections with the underground poetry community, I ranked half-a-generation ahead of Dr. Gui.

Poet Gui Minhai in the 1980s

Both our universities were located in the Western neighborhoods of Beijing, such that Dr. Gui could bike from Peking University to my small, single occupancy apartment at Beijing Industrial University within half an hour. From 1984 to 1985, he would visit my place practically every day. The company I kept at the time was mixed; perhaps he only came to direct his efforts at the motley crew that gathered in my apartment. He was shy, but not reserved, and his high spirits churned out rich discussions, all with disregard for the opinions of his big shot professors. He was heavily dependent on tobacco, as was I, though his ferocity for smoking could not be matched–he’d smoke one cigarette after the other, filling my tiny apartment with clouds of thick smoke. Through me, he made some poet and artist friends outside his circle at school. Sometimes, I’d bring him along on long car rides into the city, or take him to rest for a bit at a residence for poets and painters in the Sanlihe residential area, or ask him to tag along to a gathering of underground poets. With the solemnity of a memorial service, poets of cheerful or bright poems would one after the other get into character at those gatherings.

On weekend nights, I’d take him to parties held at the residences of Western diplomats around Sanlitun or Jianguomen. We’d have to park our bikes in the lot outside the Jianguomen “Friendship Store.”[7] Then, outside the storefront we’d change into foreign clothes–nothing more than cotton Texwood jeans, distressed and faded from so many washings, or brand-new, tight-fitting Levi’s, still indigo blue. We’d top the outfits off with a brand name red down jacket or a t-shirt, passing for overseas Chinese, and call our diplomat friends from a phone booth to let us inside. After ten minutes, they’d pick us up outside the storefront in a car, and after three or four turns, we’d be inside the diplomatic residence compound. When our car passed through security, plainclothes police and soldiers with guns sized us up with eagle eyes, but I played it cool. Dr. Gui, on the other hand, held his breath–that was a time when “Chinese or dogs [were] not allowed” to enter diplomatic residence compounds. Infiltrating the foreigner’s home amid the merriment set to deafening rock’n’roll and free, unlimited wine and beer is a memory of our 1980s youth that I share with Dr. Gui.

After graduating in history from Peking University, Dr. Gui stayed in Beijing, where he was assigned by the government to serve as assistant editor and editor of the state-run People’s Education Publishing House from 1985 to 1988. Dr. Gui took specialty training in editing, during which time he penned his own book, titled A Guide to Twentieth Century Western Cultural History (1988). To us underground writers, the 1980s were a decade spent ravenously learning about Western culture and reading Western literature. I admired Dr. Gui for getting a government publishing house to publish a book introducing Western cultural history, and gained a new level of respect for him.

Around 1989, we both left China, and fell out of contact. In my capacity as a poet and editor, I visited the United States as a literature fellow, while Dr. Gui and his wife at the time (now divorced) left for Göteborgs, Sweden. He started graduate study at the University of Goteborgs (Göteborgs universitet). In 1989, the June 4 Tiananmen Square student movement and subsequent government massacre shocked the world. This massacre was a turning point both in China’s modern history as well as in the lives of individuals of my generation.

In 1990, Dr. Gui became a Swedish citizen. In 1994, his daughter was born in Göteborgs. Because her parents were constantly by her side with care and concern, she told me, she has fond memories of her childhood.

A moving photograph–Dr. Gui and his daughter in Göteborgs

From 2000 to 2005, Dr. Gui went back to live in China, but I have no idea what what his life like during this period. The year he went back, in late August, I was imprisoned for “illegal publication” of my literary magazine, but was freed through the hard work of the U.S. State Department. After being deported to the United States, I began my life and career in exile. Dr. Gui and I passed so close in China we nearly brushed shoulders.

In 2005, Dr. Gui married his current wife, and together they left China, first immigrating to Berlin before settling down in central Germany.

Nineteen Years Apart

The next time I saw Dr. Gui was February 2007 in Hong Kong, where the International PEN Center’s Asia-Pacific regional conference, called “Chinese World of Authors–Literary Exchange,” was being hosted, marking only the second time since International PEN’s inaugural conference in 1921 that it was held in the Asia Pacific. In total, more than one hundred authors and PEN members from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and Europe participated. It was truly a long-awaited reunion for us. I noticed his dignified appearance and enlarged figure. In disbelief, I blurted out: “Ah-hai, how did this fellow get taller AND stronger? I nearly didn’t recognize you.” With a cigarette still in hand, he still spouted smoke wherever he went. But the capable and experienced man whom I met at the conference had long ago left behind that baby-faced young poet.

After a short three days, we had amassed a deeper understanding of each other’s lives. I knew he had become Gui Minhai, PhD., but he’d also published several academic works and prose anthologies. It was also that year that I read a Chinese-language translation of a book he’d sent me, The Stories Around the Swedism (2005, United Authors Publishing House)–his doctoral thesis completed at the University of Göteborgs.

At the October 2009 Frankfurt Book Fair, we met again, and together served as panelists at the Frankfurt, Germany headquarters of the International Society for Human Rights (IGFM).

Bei Ling and Ah-Hai at the forum discussion at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2009 [Photo: Zhong Weiguang]

A Prolific Politics Author with a Secret Identity

Starting in 2006, Dr. Gui discontinued writing academic works on comparative East-West history and producing prose,[8] gradually transitioning into a political writer. He focused on the high-level inner-workings of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the sexual relationships of CCP officials, and family histories of CCP leadership. He’d travel between Germany and Hong Kong every year, following the trends in modern Chinese politics from nearby.

From 2006 to 2013, he became an apprentice and intimate friend of Liu Dawen, chief editor of noted Hong Kong political culture magazine Front Line, head of XiaFeiEr publishing company, and former literary critic. Dr. Gui even had a desk at the company where he could go anytime to write or edit books. Since he already understood how Hong Kong’s publishing industry operated, he took the initiative to help Liu Dawen’s wife evaluate books, or dig them out from the warehouse. By their example, Dr. Gui became very familiar with the workings of the book publishing industry in Hong Kong.

Dim Sum restaurants are optimal for entertaining visitors to Hong Kong or family and spreading gossip, and Dr. Gui would would often invite Mainland guests there to drink and eat. Between courses, Dr. Gui listened as his Mainland guests talked nonstop, blabbering with conviction about high-level CCP relationships, internal power struggles, and erotic anecdotes, thereby collecting much first-hand information. Dr. Gui was exceptionally energetic, mentally writing and compiling books day and night. He had a keen sense for finding inside stories of high-level politics, fully utilizing the analysis, research, annotation, material sourcing, and evidence gathering skills he’d learned in the history departments at Peking University and Göteborgs University. He dashed his pen across paper, writing at least one book a month and compiling more than ten books in a year. Within only a few years, he became known as a prolific publisher in the world of banned political books.

According to information leaked in Hong Kong publishing circles, Dr. Gui published a book about Wang Guangmei,[9] wife of former PRC Chairman Liu Shaoqi,[10] in 2008 titled Autobiography of Wang Guangmei. But in March 2009, Wang’s daughter Liu Sida told a Hong Kong reporter that the book’s contents were pieced together from essays her mother had written while living as well as excerpts from interviews with reporters. According to her, the book had not changed third-person interviews into a first-person “autobiography.” Her initial response to the book was incredulous: “The things written on the cover are just not possible, we want to take legal action to determine whose fault this is, but several lawyers we consulted said it would be too hard to sue… why are people talking rubbish, concocting stories, telling slanderous lies? Publishing such a false autobiography, full of gossip and vulgarities? How is it that in a place like Hong Kong, where freedom and democracy are so strong, there is no way to investigate?”[11]

Dr. Gui wrote many books, but never used “Ah-hai,” instead using different names to publish. Though there was nothing he and his friends didn’t talk about together, he never publicly acknowledged which books he’d written. As such, friends never had the access to confirm which he’d written and which he’d edited. Just like that, he became an invisible author.

The Emergence of a Non-Native Hong Kong Publisher

It was not Dr. Gui’s only ambition to become a prolific but secret political gossip writer; he also wanted to start his own business. He’d already had a publishing house and run a distribution company, but at that time he still wanted to buy a print shop to print books. He aspired to establish a top-to-bottom publishing empire in Hong Kong. I saw these ambitions of his, and I understand them.

In 2007, Dr. Gui and Wang Jie (pen name: Chu Jin), a venerable scholar and legal translator, jointly established United Authors Publishing House. Within three years, they published 8 books. Excluding the best-seller Mistresses of the Chinese Communist Party; Secrets of Wives of CCP Officials; Women of the Shanghai Gang, which made a small profit; and QingBangWuGuo–In the Words of Jiang Zemin, the other four books were not profitable. Two literature books didn’t sell more than 100 copies, a cruel loss. The two did not go into business together again, and the publishing house did not put out any more books.

Starting in 2011, Dr. Gui established several publishing houses, including North Canal (Bei Yun He), New Vision (Xin Shi Jie), Triangle (San Jiao Di), Double Abundance (Shuang Feng), Floating Duckweed (Piao Ping), Biao Di, Breadth (Guang Du), and others. He’d alternate publishing houses, one after the other publishing banned Chinese political books. After living and publishing in Hong Kong for an extended period, Dr. Gui not only wrote or compiled books, but also had many politics writers publish with him.

Dr. Gui’s publishing houses published 4 or 5 books a month, about 50 books a year, accounting for one-third the total number of banned Chinese political publications published in Hong Kong each year. In 2013, the infamous Bo Xilai[12]scandal, involving murder and trysts, broke around the world, leaving millions and millions of Chinese in hungry suspense. That was the perfect opportunity for Dr. Gui’s publishing house. According to my rough calculation, of the hundreds of books published on Bo Xilai in Hong Kong during that time, nearly half were published by Dr. Gui’s publishing houses. According to the Guardian, one recent book published by Dr. Gui, titled The Collapse of Xi Jinping in 2017, looked at the scandal’s of China’s president.

In 2013, Dr. Gui, Lee Po, and Lv Bo, a Hong Kong expert in publishing banned Chinese politics books, jointly founded the Hong Kong Giant Dragon (Ju Long) publishing company, and started self-distributing. After decreasing the number of banned Chinese politics books they published, their distribution profits were drained.

In 2014, the three together pooled $300,000 HKD to buy Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay Bookstore, for which business had been bad and which had been operating at a loss, with a month’s rent costing nearly $400,000 HKD. The bookstore primarily sold banned Chinese politics books. To date, Causeway Bay Bookstore is considered to have the most comprehensive collection to enter into the Hong Kong publishing world.

In the last five years, Dr. Gui has already become one of the most important publishers of salacious Chinese politics books in Hong Kong. In addition to Dr. Gui, publishers including Mirror Books,[13] XiaFeiEr Publishing[14] including its subsidiary Global Industry Publishing Company (Huan qiu shi ye (Xianggang) gong si)), New Century Press,[15] and Open Books[16] have together served as the forces behind the banned Chinese politics book publishing world in Hong Kong.

Prospects for Press Freedom in Hong Kong

With a population of more than 7 million, Hong Kong enjoys freedoms of speech and press. The proliferation of freedom of information there is the only such example in the entire People’s Republic of China. As Hong Kong faces an enormous mainland readership market of 1.3 billion, half the books published in Hong Kong are political books that cannot be published in China. Among them are books where the facts are a matter of historical record, with complete and accurate evidence, that are able to endure Mainland bans. There are also books based on hearsay with sensationalized stories that would make one’s hair stand straight, stories of internal power struggles at high levels of the CCP, the rise and fall of CCP factions, and inside stories of high-level political emergencies in the CCP. Not to mention licentious page-turners featuring accounts of the mistresses and sexual encounters of high-level officials. These kinds of books, banned in China, are commonly found in Hong Kong bookstores, newsstands, and airports. A new book hits the market almost every day, sometimes becoming a bestseller. Banned publication of political books is the only glaring outlier in the publishing industry in a Hong Kong with press freedom. The biggest purchasers of these books–numbering more than one million people a month, and nearly 20 million each year–are Mainland tourists, or travelers exiting or transferring from China through Hong Kong. China, where information is censored and there is no grassroots independent media or freedom of press, is a publisher’s paradise. It has unlimited potential, attracting prolific authors and publishers such as Dr. Gui to immerse themselves in it. They very clearly recognize China isn’t just a place to make big money on a small investment through royalties and book sales. More so, it is a place where collecting source materials is difficult and the details are thrilling, like detective work. In the writing process, this kind of work yields tremendous spiritual stimulation.

The domain of banned Chinese politics books, with its secret authors, confidential sources, and thrilling revelations, is both fearful and highly competitive for publishers. Not only are there unwritten rules and regulations for publishing houses in this field, but also taboos. For example, ordinarily Chinese political books not signed with the author’s real name, or without a publicly known pen name, with content lacking in reliability, would not be published. Nor would books about the current CCP general secretary or chairman or the private lives of their families be published, in order to protect the publisher’s life. In recent years, for example, He Pin, director of Mirror Books group’s main office, has not visited Hong Kong. Dr. Gui, on the other hand, has disregarded these unwritten rules, even challenging publishing taboos. Though he keeps a low profile, he pays no mind to the danger he is in. He spends three months every year living in Hong Kong. His status as a Swedish citizen served as a psychological safeguard in these circumstances.

A sense of mourning has overcome Hong Kong since Dr. Gui and his three colleagues were “disappeared” more than 40 days ago. Those in the world of Hong Kong’s banned Chinese politics books panic at the slightest move. The absolute freedoms of speech and press in Hong Kong are now in decline. Though press freedom exists there, the self-censorship imposed by publishing houses is even more restrictive. In a Hong Kong with no media to serve as watchdog, authors and publishers have to face the “consequences” each time they put out a new book. The spell of self-censorship has been cast upon the heads of all publishers of banned Chinese politics books. This is the state of “press freedom” in Hong Kong under China’s shadow.

Mr. Gui’s “disappearance” is, so far, the most terrifying outcome a Chinese publisher and author could encounter. The mysterious force that entrapped him did not merely want to prevent his continued publication of these Chinese politics books. This force didn’t only want to understand, what did he write? What they really want to know is: who are the authors of books he has published? Who are the sources that provided information to him? Who was frequently dealing with him over email? And what were they giving him?

The information on Dr. Gui’s computer was hacked, his email password compromised, his mail read. I fear that every author of one of those books, every person with whom he had electronic contact, every source who supplied him information, all will face uncertain consequences.

Conclusion

Dr. Gui was disappeared in Thailand. Looking at the present circumstances, the Thai government and police are responsible for executing the following investigations:

- Collecting fingerprints from inside Dr. Gui’s apartment in order to identify the four men who entered his apartment;

- Checking whether Thai customs has a record of Swedish citizen Gui Minhai leaving the country on October 17;

- Looking for the location of the car Dr. Gui was driving when he disappeared on October 17.

Dr. Gui is a genuine risk-taker in the publishing world, an atypical publisher who has taken off in the Hong Kong publishing world in recent years. Even more so, he is a master player in the fiercely competitive Hong Kong publishing industry who has broken the rules–written and unwritten–of the industry. He has an extraordinary sense of the appetite shared by millions and millions of potential Chinese readers for voyeuristic Party politics and the depraved acts of Party leaders. His success in flooding the Hong Kong publishing world with such works, and even his work’s abrupt halt now, have become another page in the annals of Hong Kong publishing history.

Since Dr. Gui told his wife over WeChat in mid-November not to fly to Thailand, he has made no contact whatsoever.

From where does the mysterious force that captured Dr. Gui across borders come? From which country? The answer is all but certain.

Sharing a common fate, there is no doubt that the threat presented by this force draws nearer to Hong Kong’s press freedom, Hong Kong publishers, and Chinese politics writers.

[FIN]

Special thanks to:

Boxun’s Chinese language website, author Meng Liang, Mr. Li Fang in the Netherlands, Gui Minhai’s family, the property management office at Dr. Gui’s apartment building in Pattaya, Pan Yongzhong, U.K newspaper the Guardian, and the many individuals whose names cannot be divulged.

Appendix I: November 7, 2015, Bei Ling’s “Reflections on Ah-hai’s ‘Disappearance’”

I spoke with Dr. Gui’s wife ten hours ago, and she very clearly told me ‘he’s well.’ Even so, after five hours spent believing her and three spent thinking it over, I strongly doubt he’s really ok. My question is this: where is exactly is Dr. Gui? In what place is he ‘well’? Has he been kidnapped and taken back to China, or is he still vacationing in Thailand? Why have they not allowed him to appear and report to the media that he is ok? How exactly did this happen?

All signs suggest he has come under the control of some kind of mysterious force, to the extent that, regardless what what he says, I fear it will be manipulated behind his back by this force. The signs include: it has already been 15 days since he contacted the contractors renovating his apartment in Hong Kong to talk through the details of the renovation, whereas before he would call nearly every day; he confirmed he’d be in Hong Kong on October 25 to receive a poet friend visiting from Shanghai staying at his apartment, but he has yet to return to Hong Kong so the poet found other accommodations; also, though he’s had phone contact with his wife, the calls have been rushed, and it seems the media attention on his whereabouts pushed him to tell his wife he’s ‘ok.’ This all points to one conclusion: he’s being controlled.

This is my suspicion! If only I were wrong…

From my experience being detained in prison in China, I know prisoners’ families ordinarily are managed by police, led to believe that if they keep quiet and comply, then this big problem will go away. Moreover, the psychology underlying an authoritarian society’s actions allow it to believe that through connections and back doors, it can make someone free. This fantasy is well demonstrated. Take Yiu Mantin as an example. When he was first taken, his family didn’t disclose it to the public but rather also reported ‘he’s well.’ They thought privately seeking help from an intermediary in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference or the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government in Hong Kong, and relying on connections could bring Mr. Yiu back to Hong Kong. When Hong Kong Legislative Council members including Zhang Mao wanted to hold a press conference to make Mr. Yiu’s case public, his wife was absent, further delaying the process three months in total. In the end, Yiu Mantin was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Thus, regarding the matter at hand, we must not blindly trust what the family says. I only need Ah-hai to appear just once, to tell us just one thing–where is he? Is he free, or not? No matter if it’s just one sentence, as long as he tells us where he is, that’s the only important thing.

In the early stages, we were led to believe he was safe, and so didn’t have the strength of conviction to ask for help or call for support. Perhaps we missed the best time to save him. I simply could not believe, that while his employees and associates were detained in Shenzhen, he was somehow alright…

Today, Hong Kong’s Apple Daily reported Causeway Bay Bookstore manager Lin Rongji called his wife after being detained in Shenzhen–further proof of my suspicions.

Thinking it over, there is no way I believe Ah-hai is ok, and now, I want to convince his wife that I have come to this conclusion after lengthy consideration. Everyone, please do not lower your guard…

Dr. Gui is also my friend of thirty years. Now we must seize this important moment to help him by bringing the attention of the international community–only then can we save Dr. Gui. I will work as hard as possible to utilize my connections with the German Foreign Affairs Ministry councilor of human rights and other agencies as well as Western media contacts. Through XXX’s hard work, we have contacted the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to intervene and save this Swedish citizen. Dr. Gui is also a permanent resident of Germany, so the German government will likely also have a strong response to this situation.

The PEN Center’s statement might be insignificant, but we still must issue it and translate it to inform the International PEN Center and the PEN American Center. It is our moral duty to make clear the PEN Center’s absolute intolerance of this kind of behavior.

The International PEN Center so far has been insignificant in the international community, and we [the ICPC] have no way to match its pooled power. This is something Jennifer Clement, the International PEN Center’s new president, touched on in her remarks when she took office. Soon after she and I talked about the current situation, and she said the focus of her work would be to make the International PEN Center resemble organizations like the International Cities of Refuge Network, Doctors Without Borders, or Amnesty International, thereby becoming an international organization with the weight to be valued by the international community. The International PEN Center–let alone the ICPC–has yet to achieve this status.

These thoughts thus are drawn from several decades of life experiences and have nothing to do with my position as president. In sending this to our community, I only want it to be shared among members.

Appendix II: China: Serious Concerns about the Disappearance of Four Hong Kong-based Publishers

The International Publishers Association and PEN International are alarmed at reports that four people associated with a publisher and bookstore in Hong Kong famous for producing and stocking books critical of the Chinese authorities have gone missing. Gui Haiming, the Swedish owner of Sage Communications, along with general manager Lu Bo, store manager Lin Rongji, and staff member Zhang Zhiping have all been reported missing. Fears are growing that they may have been detained by the Chinese authorities.

The President of PEN International, Jennifer Clement, said, ‘PEN International is deeply concerned by the recent reports of four missing publishers in China. If it’s confirmed that they are in detention, it will be yet another blow to the declining situation for freedom of expression in the country. Chinese authorities should investigate these reported disappearances and immediately clarify the situation.’

IPA President, Richard Charkin said, ‘We are seriously concerned for these people’s safety. If they have indeed been arrested, then this is another example of the Chinese Government’s campaign to try to silence dissent in Hong Kong. The IPA calls on the Chinese Government to immediately declare whether these four people are indeed being detained and if so, on what charges. In any event, we ask the Chinese Government to do everything in its power to assist in locating the publishers and allowing for their safe return.’

See more at: http://www.pen-international.org/newsitems/china-serious-concerns-about-the-disappearance-of-four-hong-kong-based-publishers/#sthash.j4h4mPKr.dpuf

A photograph of the author in October 2015

[1] Dr. Gui Minhai, of Manchurian descent, was born in 1964 in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province. He is an alternate member of the International Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) Board and a former coordinator of the ICPC Translation and Linguistic Rights Committee. In 1985 he graduated from Peking University History department. From 1985 to 1988, he served as editor of the People’s Education Publishing House. In 1988 he went to study at Göteborgs Universitet in Sweden, becoming a Swedish citizen in 1990. In 1995, he became a professor at the East Asia and Southeast Asia Research Center at the University of Göteborgs, where he earned his doctoral degree in 1996. In 2003 he immigrated to Germany. He started renting a long-term residence in Hong Kong in 2010. Starting in 2007, his publishing work often took him back and forth between Germany and Hong Kong, and that year he and Wang Jie jointly established a publishing house in Hong Kong. He has launched eight small publishing houses. In 2013, he jointly established Hong Kong’s Mighty Current Distribution Company with Lee Po and his wife and Lv Bo. In 2014, they acquired Causeway Bay Bookstore.

[2] With Bei Ling, one of the co-founders of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC), and a poet. He moved to the United States in 1995, and in 2006 immigrated to Hong Kong. From 2008 to 2012, he served as chief editor of Hong Kong’s Morning Bell Press. In 2010, he established Fountainhead Books. He first met Dr. Gui in 1985.

[3] See Appendix 1, “Reflections on Ah-hai’s ‘Disappearance.’”

[4] On November 16, Dr. Gui’s wife through a mutual friend in Germany passed to me her three requests: (1) Do not intervene in Dr. Gui’s business again; (2) Do not scare her by claiming Dr. Gui’s disappearance was due to kidnapping again; (3) Do not discuss Dr. Gui’s disappearance with media again, as only she possesses the right to do so.

[5] See Boxun news, website: http://news.qq.com/a/20151110/010895.htm; http://news.qq.com/a/20151110/021181.htm.

[6] See appendix II, China: serious concerns about the disappearance of four Hong Kong-based publishers.

[7] The Friendship Store was a PRC state-run store originally intended for foreigners, diplomats, etc., specializing in selling imported Western goods and quality Chinese crafts.

[8] Dr. Gui’s works on Eastern and Western comparative culture and politics and academic books include: Guide to Twentieth Century Western Cultural History (1988), The Mythology and Folklore of Scandinavia (1992), Feudalism in Chinese Marxist Historiography (1993), Ten Years of Yongzheng: The Story of that Swedish Vessel (2006), Dark Secrets of China’s Slave Labor (2007), etc. In addition, he wrote essay-style books and a large volume of poetry and commentary, including I Give You the Black Forest: Essays from Ah-Hai (2007).

[9] Wang Guangmei (1921-2006), ancestral hometown of Tianjin, was born in Beijing. She was the sixth (and last) wife of Liu Shaoqi, head of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and second chairman of the People’s Republic of China.

[10] Source: Tie Hua, “Net of Iron Will,” March 10, 2009.

[11] Website: http://wap.tiexue.net/3g/thread_3411992_1.html.

[12] Bo Xilai (1949-), son of senior CCP senior official Bo Yibo, was born in Beijing. He participated in the 16th and 17th CPC Central Committees and the 17th CPC Politburo. Starting in 2007, Bo Xilai served as the CCP secretary of Chongqing municipality. In 2012, he was demoted and dismissed from the CCP for bribery, corruption, and abuse of power. In 2013, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. In addition, Bo Xilai’s wife Gu Kailai was handed down a deferred death sentence in 2012 for her suspected murder of British citizen Neil Heywood in 2011. Allegedly, Heywood was a personal assistant to the Bo family, and had intimate relations with Gu Kailai.

[13] Mirror Media Group was established in Canada in 1991 under the name Mirror Books. “Mirror” takes its meaning from the phrase, “The mirror does not lie, only reflects history.” Mirror Media Group’s subsidiaries include Mirror News Agency, Mirror Publishing, Mirror Magazine, Mirror TV, and a bookstore. In 1993, its headquarters moved to New York City. Its main bases of operation are New York, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

[14] XiaFeiEr publishing was established in 2001, and its name is a homophone for Paris’ “Eiffel Tower.” XiaFeiEr has already published more than 200 books on Chinese politics, current affairs, society, people, financial technology, military affairs, and other topics. It is Hong Kong’s biggest publisher of political works.

[15] New Century was established in 2005 by Bao Pu, son of Bao Tong, who served as political secretary to former CCP general secretary Zhao Ziyang. New Century mainly publishes banned Chinese politics books.

[16] Open Books was established by Jin Zhong, its chief editor, in order to publish books on the history of Chinese politics. In January 1987, Jin Zhong published the first monthly edition of Open Magazine in Hong Kong. The magazine mainly covers commentary on political developments in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

俄羅斯反建制團體暴動小貓(Pussy Riot)原本會出席巴丟草展覽的開幕禮,但得悉活動取消後到大館抗議。圖片版權BBC CHINESE

俄羅斯反建制團體暴動小貓(Pussy Riot)原本會出席巴丟草展覽的開幕禮,但得悉活動取消後到大館抗議。圖片版權BBC CHINESE