http://video.udn.com/news/499498

會員簡介

独立中文笔会为赵常青、张宝成、梁太平被拘留之声明

獨立中文筆會就本筆會會員趙常青、張寶成、

本會會員趙常青、張寶成、梁太平及馬新立、徐彩虹、

本筆會強烈要求北京警方立即無條件釋放上述因表達和思想自由被剝

獨立中文筆會〔ICPC〕是國際筆會——

纪念六四何罪之有?!—独立中文笔会述评

纪念六四何罪之有?!—独立中文笔会述评

《左传》中有这样的话:“要想加害一个人,还发愁没有理由吗?”古代封建社会要想加害一个人,一定会找出莫须有的罪名。不幸的是,现代中国的当权者,比起古代加害无辜有过之而无不及。本会会员赵常青、张宝成、梁太平等,因和几位朋友在家纪念六四27周年,于6月1日,被北京市公安局丰台分局以“寻衅滋事”罪名刑事拘留,现被羁押在北京丰台区看守所。因同一事件被拘的,有马新立、徐彩虹等。赵常青妹妹曹雪梅女士。我们对此严重关注!

首先请问:纪念六四有罪吗?据国家教委统计:1989年全国先后有四千万人次参与了民主运动,而八九民主运动的最主要诉求就是:民主改革与反腐败。当局调动了几十万大军,展开了天安门战役,成千上万的学生和市民被当作“反革命”镇压,死伤无数。枪声一响,变偷为抢,如今罄竹难书的腐败,不正是镇压六四导致的后果吗?如今中国最需要的不正是民主改革与反腐败吗?纪念六四,是还历史一个公正,还人民一个正义,还政治一个公道。

提醒当局:在所有的民主国家里,反党都不是罪,反对某个政府领导人也不是罪。唯独在专制体制下,纪念一下民主运动也是罪。反对某个国家领导人更是大罪。这种迂腐的思维,甚至落后于越南及缅甸。只能和北朝鲜金正恩世袭王朝媲美。

特别奉告:我们严正要求当局立刻释放所有因纪念六四而被羁押笔会会员及其他民众,允许律师为无辜者提供法律援助。如果某些权势者以为用手遮住天空,那么,你们就继续表演吧。但历史不是可以被人任意打扮的妓女,历史的本来面貌是掩饰不住的。历史上用刑苛酷而丧国的例子还少吗?

高行健:以文學、藝術呼喚文藝復興

以文學、藝術呼喚文藝復興

文:高行健

這全球化的當今時代,政治和廣告無孔不入,連文化也充分市場化,

人類歷史上政治權力對文學藝術的干預不是沒有先例,

誠然,

Photo Credit:高行健高行健,〈孤舟遠影〉,攝影作品。

問題進而又在於現今世界離開了政黨政治,

以人權為標榜的自由主義也是一種意識形態,

作家藝術家如果不甘心充當這樣或那樣的政治的點綴,

然而,市場法則全球化鋪天蓋地的現今世界,

Photo Credit:高行健高行健,〈夜間行歌〉,水墨,2016。

超越政治和市場不謀求功利的文學藝術在現今這時代是否可能?

這樣的文藝首先得出於作家藝術家自身的感受,

這樣的作品自然超越時尚,毫不理會權力和媒體倡導的流行趣味,

這種作品的價值更在於是否深刻觸及人的生存條件及其困境,

這裡講的真實而非新聞的實錄或歷史的紀實;

Photo Credit:高行健高行健,《洪荒之後》,單頻道錄像,

這種創作當然無須他人的指令,更沒有現成的模式,

這樣的作品並非是民族和時代必然的產物,而是一個個獨特的個案。

這裡談的既然是創作,與其討論時代提供的社會條件,

相比之下,當今的作家藝術家畢竟幸運,只要能逃離集權專制,

再一輪的文藝復興是否可能?

Photo Credit:高行健高行健,《側影與影子》,單頻道錄像,

把美學的顛覆與時尚的炒作丟到一邊,文藝復興也就順理成章。

這樣的文藝復興當然不由民族國家來宣導,

這樣的文藝復興只能出於作家藝術家個人的認知,

這樣的文藝復興固然需要各種各樣不牟利的文化基金的贊助,

這樣的文藝復興現今這時代並不囿於某些特定的國家和地區,

Photo Credit:高行健高行健,〈霧雨〉,攝影作品。

這也正是現今呼喚文藝復興的根據,

且不必預言人類的未來如何,何況這樣的烏托邦許諾,

哲學、宗教和文學藝術是人以不同的方式對自身生存的一番認知。

而文學與藝術在政治與市場雙重擠壓下,

Photo Credit:聯經提供

這樣的文藝復興正取決於作家藝術家的良知與覺悟,

這樣的文藝復興之所以可能,如同歷史上已經有過的陰暗的時代,

這樣的文藝復興當然首先來自作家藝術家深刻的認知,

這樣的文藝復興令作家藝術家得大自在,

這樣的文藝復興可以就在當下,一步一個腳印,步步登高,

這樣的文藝復興其實又心心相印,建構之時,

這樣的文藝復興既然建立在人性相通的大前提下,

這樣的文藝復興就始於作家藝術家手下,一旦覺醒到有其必要,

這樣的文藝復興可不是不是不可能的。

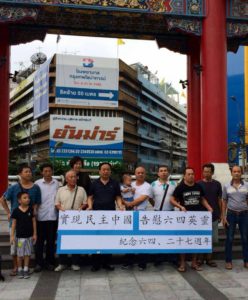

旅泰受中共迫害公民纪念六四活动

旅泰受中共迫害公民纪念六四活动

2016年6月4日,流亡泰国的中国受迫害公民汇聚唐人街,与来自美国的民运人士韩武(中国民主党全国联合总部秘书长)专程赶来泰国与我们一道共同纪念六四,抗议中共的暴行,为实现中国的民主事业而奔走,同时呼吁中共停止迫害中国公民。

韩武指出:纪念8964事件,不仅仅是缅怀已经被中共屠杀的仁人志士,更是要激励后来者,以更大的勇气,更坚定的决心扛起前辈们的民主大旗奋勇向前,不能畏首畏尾。我们纪念六四,到今天已经不是反思的问题,而是要牢记六四惨案,以烈士们的鲜血激励全国的民众团结起来,向中国的一党专制发起冲击,实现民主中国,建立自由、人权、民主、宪政的新社会。在当前中共打压最残暴的时期,我们一方面要善于和中共当局周旋,另一方面也要用智慧和中共战斗。

黎小龙认为:要在法律的框架内清算中共的屠杀。

颜伯钧说:我们被迫流亡海外的中国公民应该团结一心,众志成城。

于艳华认为:当前国内有七位勇士因为纪念六四而纷纷被抓捕,这些人以前都是新公民运动的干将,我们今天纪念六四也为他们的安全呼吁。

活动过程中,大家纷纷表态,梁山桥老先生对于中共屠杀义愤填膺,张维,曹劲柏也是大声指责中共的暴行,最近逃亡过来的张建祥详述牺牲人员的惨烈。大家说到动情处,宴奇恩流下了悲愤的眼泪。黎光敏,刘晓赢也就亲身经历说出了自己的感受,聂保国是一宗教人士,他从宗教的角度阐述了对这一事件的认识。

整个活动全体参加人员为六四事件死去的英灵默哀一分钟。之后发起了呼吁最近因为几年六四事件而被捕的赵常青、张宝成、李蔚、马新立、徐彩虹、李美青、梁太平,大家呼吁中共当局放下屠刀,立即放人、悔过自新,以减少对全体中国人民的伤害。

活动也呼吁中共当局就郭飞雄的身体原因,予以人道主义关怀,并就唐荆陵、王清营、袁新亭等三人被迫害进行了呼吁。

因为同属逃亡到泰国的中国受迫害公民,大家也纷纷对姜野飞、董广平的遭遇有一种同病相怜的感情,大家表示深深的愤慨和痛恨,一定要不畏恐惧勇敢的战斗。大家呼吁国际社会继续予以高度关注,希望有能力的国际组织、政府和个人能够帮助呼吁中共当局不要继续迫害这两位已经获得难民身份的受迫害者。

让参与活动的每一位人员感到愤怒的是中共当局对709人权律师的迫害,由此全体人员希望全世界关注709人权律师。

本次活动参加人员有:韩武(中国民党全国联合总部秘书长)、梁山桥、黎小龙、颜伯钧、于艳华、张维、张建祥、曹劲柏、宴奇恩、黎光敏、刘晓赢、聂保国。

中国民主党全国委员会东南亚委员会主席程维明对活动予以赞助。

逃亡泰国的中国受迫害公民(泰国难民之家)

中国民主党全囯联合总部东南亚分部

中国民主团结联盟东南亚分部

中国民主党全国委员会东南亚委员会

中国社会民主党东南亚分部

中国公民联盟

独立中文笔会代表团参加国际笔会第81届大会

独立中文笔会代表团参加国际笔会第81届大会

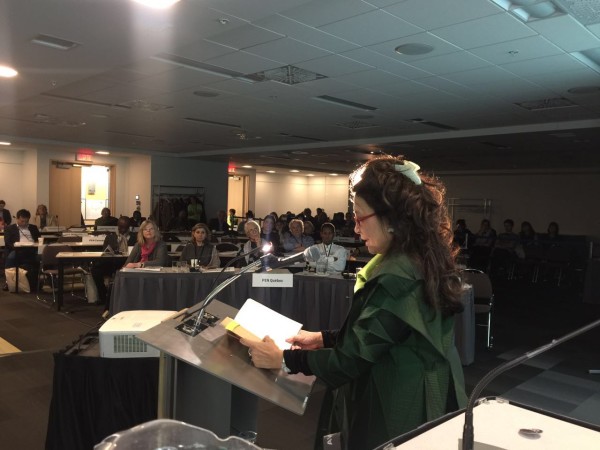

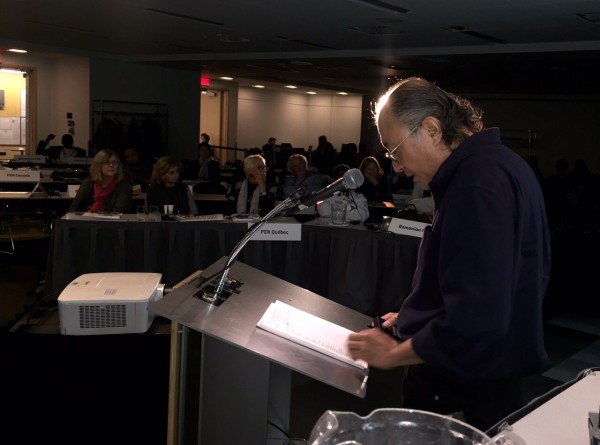

(加拿大魁北克讯,2015年10月12日)国际笔会第81届大会将于10月13-16日在加拿大魁北克召开,来自全世界80多个国家的250多位作家济济一堂,交流文学创作与翻译、商讨捍卫言论自由。独立中文笔会派出由六位成员组成的代表团参加此次国际笔会大会,代表团由贝岭会长带队,成员有张戎、雪迪、孟浪、盛雪和司鹏程。

10月12日晚,国际笔会魁北克年会在新落成的“文学图书馆”举行欢迎酒会,这座“文学图书馆”落成才四天,是专门为此次国际笔会大会建造,图书馆收藏的文学书籍均为法语文学作品;当晚“魁北克文学节魁北克文学之夜”也在一座剧院内举行,魁北克笔会的作家们朗诵了他们的法语文学作品,现场还有音乐演出。先期到达魁北克的本会代表贝岭、雪迪、孟浪、盛雪参加了欢迎酒会和文学之夜的活动。

10月14日下午,国际笔会第81届大会在主场大会后举行“中国文学专场”(Chinese Literature in Focus),此为国际笔会历史上首次于年会期间举办“中国文学专场”,是独立中文笔会自创会以来首次获得以文学专场形式在国际笔会的文学节上出场,也是本届国际笔会大会上仅有的两个“文学专场”之一。届时,张戎将以“我如何成了一名作家”为题进行演讲并朗诵她的作品,贝岭、雪迪、孟浪、盛雪也将随后以中文朗诵他们的诗作,全场用大屏幕呈现作品的英文和法文翻译。

此次魁北克文学节于国际笔会年会特辟“中国文学专场”,使独立中文笔会得以用“文学”与会,也是国际笔会“弘扬文学”之重要成就。正如在今天的欢迎酒会上国际笔会会长约翰·索尔所说的:国际笔会首先是文学组织,然后才是捍卫言论自由的人权组织,没有了文学,也就没有了言论自由的基础。

国际笔会第81届年会举办“中国文学聚焦”专场

国际笔会第81届年会举办“中国文学聚焦”专场

(加拿大魁北克讯,2015年10月14日)10月14日,第81届国际笔会年会在加拿大魁北克召开期间,举办了“中国文学聚焦”(Chinese Literature in Focus)专场。

“中国文学聚焦”(Chinese Literature in Focus)专场在当地时间下午5时开始,首先由张戎作25分钟的英文讲演,主要叙述了她从事文学创作的经历,介绍中国作家目前所处的境况,此后用五分钟时间朗读了她的作品《鸿》中的精彩章节。张戎的演讲和朗读之后,便有独立中文笔会四位会员朗诵他们的诗歌,贝岭、孟浪、盛雪和雪迪依次登台朗诵自己的中文诗歌作品。贝岭朗诵了他自己的三首诗作:“为梦留下为时间”、“放逐”和“纪念—为1989六四受难者而作”,孟浪朗诵三首他创作的诗歌:“世界图景”、“时间就只是解放我的那人”和“在中国…… ——为‘六四’二十一周年而作“;盛雪朗诵的是她的诗作“海与岸——哀在多佛尔死难的 58 名同胞”;雪迪朗诵的三首诗歌为:“回忆”、“威金人旅馆”和“天堂的通道”。四位作家在朗诵自己诗作的同时,会场的大屏幕上播放出他们朗诵诗歌作品的英文和法文译文。

参加这一活动的国际笔会代表对本会作家的作品表现出了极大的兴趣,活动获得了巨大成功,为此次国际笔会大会增添了色彩。

此次“中国文学聚焦”是国际笔会历史上首次于年会期间举办的中国文学专场,也是独立中文笔会自创会以来首次获得以文学专场形式在国际笔会的文学节上出场。

魏京生:文革与六四

魏京生:文革与六四

最近网上和传媒界最热烈的话题,就是文革五十周年。说法越来越深入,也越来越分歧。有说文革从1964年四清运动时候就开始了;也有说从57年反右的时候就开始了;还有说三年大饥饿是文革发生的原因;从文革时的很多现象上看,也可以说从五四运动时候就开始了。或者说是五四运动的激烈反文化运动的延续。

把这些说法综合起来的结论,就是文革绝不是一场突发的偶然事件,而是一百多年来中国学习西方的运动走上歧途的必然结果。由于共产党的乌托邦思想,和马克思主义的专制暴政的设计,最终造成了文化大革命这场触及全民族灵魂的的浩劫。相比于文化和精神的损失,物质的损失可以说微不足道。

中华民族之所以成为一个伟大的民族,传统的文化和道德精神体系,起了极其重要的作用。现在平心静气来回顾,中华文明的道德精神体系,和西方发达民族的道德精神体系大同小异。其本质的差异性甚至小于西方各国文明之间的差异。把精神文明的表层现象抽象掉之后看他们的本质差别,就知道那基本上就是所谓的普世价值,差别也可以说微不足道。

所以在西方传来的暴政文化的压迫下,文化冲突带来的反抗,就成为上层精英斗争的主线。毛泽东和共产党在文化层次上不断发动文化革命,正是维护其暴政的意识形态需要。而文革期间对人的灵魂的伤害和毒害,是文革留给中国人的最重要的遗产。

由于文革结束的偶然性,共产党内斗中的另一派接管了政权,并且继续了一党专政的暴政体制。所以对文革的深刻反思被禁止,并被引导向比较浅层的忆苦思甜的方向。同时继续沿用中共邪恶的仇恨政治,把党内斗争中失败的一方当作替罪羊;同时把文革中被中共利用过的红卫兵和造反派当作替罪羊。掩盖了中共本质上的邪恶;掩盖了中共统治阶级的集体罪恶。

继续坚持暴政的体制,那么就必然要保护维持暴政的意识形态,也就是邓小平总结的四个坚持,和毛泽东时代创造的神话。继续用没有共产党就没有中国的神话来毒害中国人的精神世界,继续着破坏中国传统精神文明和普世价值的工作。这就是造成现代中国社会道德堕落,精神空虚的原因。

由于文革时期建设乌托邦的教训,后文革时代中共不得不放开市场经济的门缝。从门缝中挤出来的一小部分人富裕起来了,新的资产阶级产生了。而这个资产阶级中的大部分人和权力之间有着不可分割的关系,所以这就是名副其实的官僚资产阶级。

这个利用权势发财的官僚资产阶级,必然和社会产生尖锐的矛盾。因为中国的社会和文化,两千多年来早就习惯于市场经济和公平的法律。由于民间文化的普及程度,公平和公正的原则深入民心,不是一场文化革命就可以消灭的。所以专制暴政和贫富不均,必然和顽固的中华文化传统,以及从西方传进的普世文化价值观发生尖锐的对立。

这种对立,从中共执政以来就没有停止过。经过右派运动和文革造反,一波强似一波。从文化精英阶层到普通百姓,范围逐渐扩大。到文革的末期,发展到四五天安门运动,和文革结束后的民主墙运动。已经明显产生了对共产党统治的威胁。

在多数共产党人还沉浸在报仇雪恨和改革残害过他们的体制的氛围中之时,邓小平及时提醒了重回权力地位的官僚们;不维护一党专政的意识形态,就无法维护专制的权力体系。整个八十年代,邓小平及其帮凶们巧妙地和残酷的镇压了此起彼伏的民主运动。包括毫不留情的清除了党内的动摇分子,直至最高领导人总书记。

发生在八十年代最后一年的天安门民主运动,就是共产党暴政和中国文化传统以及普世价值之间不可兼容的矛盾的总爆发。十年的改革开放,只是对少数接近权力的人和外国合作者的开放。大多数老百姓仍然只是马克思所说的生产要素;而且是马克思论证的合理合法的剩余价值剥削后的生产要素。当然也只能享受维持生产要素所需要的最低生存条件。

但是两千多年市场经济的意识形态不接受这种马克思主义理论。中国老百姓的传统意识形态不认为剩余价值理论是公平的理论,也不接受专制暴政制造的机会不均等,和因为这个不均等造成的贫富差距。腐败成为发动反抗的最刺激的理由;民主和平等是躲在背后的潜台词。直到即将遭受镇压之前,才有一小部分人丢掉幻想,把民主女神的塑像矗立在天安门广场。

邓小平和共产党则是清醒的认识到这场新的民主运动的最终目标,只能是针对共产党的专政。最终的结果,就是从打着共产党旗号的反腐败,走向推翻一党专政。四十年的洗脑工作,并没有清除中国人的自由平等的意识形态,和要求公正法制的传统文化。

意识形态斗争的失败,只能动用残酷的镇压来补充。这就是马屁文人所说的无奈的屠杀,为了经济发展的屠杀。随后发生的苏联东欧和台湾的民主运动产生了截然不同的结果,对照之下我们可以更深入的反思失败的原因。

文章来源:RFA

The History of PEN International

The organisation known today as PEN International began in London, UK, in 1921, as simply PEN. Within four years there were 25 PEN Centres in Europe, and by 1931 there were several Centres in South America as well as China.

As the world grew darker just before the outbreak of war in 1939, PEN member Centres included Argentina, Australia, Bolivia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Egypt, India, Iraq, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Palestine, Uruguay, the US and others. All the Scandinavian countries were accounted for in the membership, as well as several countries in Eastern Europe. Basque, Catalan and Yiddish Centres were represented, too.

For over eight decades, then, we have been a genuinely international organisation, encompassing a wide array of cultures and languages, and today the overwhelming majority of PEN International’s 145 Centres come from outside Europe.

PEN was one of the world’s first non-governmental organisations and amongst the first international bodies advocating for human rights. Certainly, we were the first worldwide association of writers, and the first organisation to point out that freedom of expression and literature are inseparable – a principle we continue to champion today and which is expressed in our Charter, a signature document 22 years in the making from its origins in 1926 and ratification at the 1948 Congress in Copenhagen.

PEN has grappled with the challenges to literature and freedom for nearly one troubled century, beginning just after World War I to the buildup and eruption of World War II, then throughout the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union and into today’s more nuanced climate worldwide. It has responded to modern history’s most dramatic turns, and its heroes have included the most celebrated intellectuals of each era as well as countless tireless and dedicated members fighting to ensure that the right to write, speak, read and publish is forever at the heart of world culture.

‘PEN’: What’s in a Name?

Our name was conceived as an acronym: ‘Poets, Essayists, Novelists’ (later broadened to ‘Poets, Playwrights, Editors, Essayists, Novelists’). Following World War Two, as the notion of an executive developed (see below), PEN became known as International PEN, comprising a growing number of Centres around the world. Over time, as our membership expanded to include a more diverse range of people involved with words and freedom of expression, the aforementioned categories no longer exclusively defined who could join. Today, PEN is simply PEN. In 2010, as part of a general rebranding, the organisation was renamed PEN International.

Genesis: a new kind of dinner club

Catharine Amy Dawson-Scott, a British poet, playwright and peace activist, founded PEN as a way to unite writers after the devastation of World War One. It was, at first, nothing more than a dinner club, providing a space for writers to share ideas and socialise. PEN clubs would be set up in other European cities, so writers on their travels would have a place to meet friends and fellows.

Guests at Dawson-Scott’s dinner included PEN’s first president, John Galsworthy, who spoke of the possibilities for an international movement – a ‘League of Nations for Men and Women of Letters’.

A question of politics

PEN held its first Congress in 1923, with 11 Centres taking part. Throughout the 1920s, PEN was unique in bringing writers together regardless of culture, language or political opinion – especially considering the political turmoil the world had begun to experience. In fact, one of the founding ideas guiding PEN was expressed as ‘no politics in PEN Clubs – under any circumstances’. PEN saw itself standing for freedom of expression, peace and friendship, not political debate.

By 1933, however, this thinking was challenged by the growing shadow of National Socialism in Germany. The delegates attending PEN’s Congress in Dubrovnik that year found it impossible to ignore the growing climate of repression and intolerance.

The German dissenters

Even as early as 1926, at PEN’s fourth Congress in Berlin, tensions had arisen between the German PEN Club and the PEN community in general. A number of young German writers – Bertolt Brecht, Alfred Döblin and Robert Musil amongst them – expressed their concern that PEN in their country didn’t represent the true face of German literature. They met with Galsworthy to express their dismay. The playwright Ernst Toller insisted that PEN could not ignore politics – that it was everywhere and influenced everything.

Burning books, burning indignation

In 1932, at the Congress in Budapest, an appeal was sent to all governments concerning religious and political prisoners. Galsworthy issued a five-point declaration – another stage in the evolution of the PEN Charter as it is today.

The following year saw political tensions rise to an unprecedented level within PEN. The British novelist H. G. Wells, who became PEN’s president in 1933 following Galsworthy’s death, led a campaign against the burning of books by the Nazis in Germany. German PEN failed to protest and, moreover, attempted to prevent Toller (who was Jewish) from speaking at the Congress in Dubrovnik. It subsequently had its membership withdrawn. ‘If German PEN has been reconstructed in accordance with nationalistic ideas,’ a statement from PEN read, ‘it must be expelled.’

Writers behind bars: two early cases

By the late 1930s, PEN was active in appealing on behalf of writers and protesting against their treatment. The case of the Hungarian-born Arthur Koestler (then a journalist), who had been imprisoned in Fascist Spain and sentenced to death, was one early success: he was freed soon after PEN campaigned for his release.

(The great Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, on the other hand, was executed shortly after his arrest; tragically, PEN could only take action upon receiving a telegram – too late – informing the organisation of the danger he had faced. A resolution at the 1937 PEN Congress in Paris paid homage to Lorca and expressed dismay to the people of Spain at his death. This response, in fact, was likely a factor in the positive outcome of Koestler’s case.)

Postwar PEN

PEN looked very different at the end of World War Two. The original concept behind its creation as a club welcoming writers regardless of race, religion or creed had been fractured by reality. New groups of writers in exile had also been established in London and New York during the war.

Pressing issues faced PEN, such as how to deal with writers who had supported National Socialism in Germany and elsewhere, and how to ensure that the growing international PEN community could come together regularly enough and contact each other quickly when necessary. Thus the Executive Committee was formed.

In 1949, following the passage of a resolution introduced by the PEN American Centre, PEN acquired consultative status at the United Nations as ‘representative of the writers of the world’.

By the 1950s, PEN members were discussing the formation of a committee to examine cases of writers imprisoned or persecuted for their work and opinions. The Writers in Prison Committee came into being as a result, in April 1960. Despite – or perhaps because of – the Cold War’s polarising effect on the world, PEN’s influence spread internationally.

Wole Soyinka and a certain letter from Marilyn Monroe’s husband

In 1967, under the presidency of American playwright Arthur Miller, PEN appealed to Nigeria on behalf of a playwright whose name was, then, not widely known outside his country. Wole Soyinka had been marked for immediate execution by the country’s head of state, General Yakubu Gowon, during the civil war over Biafran secession.

A businessman conveyed the letter from PEN to Gowon, who noted the name of its author and asked he was in fact the same man who had married Marilyn Monroe (which indeed Miller had, in 1956). When assured that the very same man was asking for the Soyinka’s release, Gowon released his prisoner – who then left the country and, of course, went on to become one of the world’s most eminent poets and playwrights, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986.

Russians unmoved

Miller also travelled to the USSR to meet with the Union of Soviet Writers, and was told bluntly that Soviet writers wanted to join PEN but for one major obstacle: the Charter. Miller made it clear that altering the Charter to suit the Soviets was not up for discussion, adding that the vision it articulated was what united PEN worldwide. He nevertheless made sure that dialogue across the East–West divide was kept open; but it wasn’t until 1988 that Russian PEN was finally formed.

Over the next three decades to the turn of the millennium, PEN’s reach and impact were felt in most regions of the world. Our voice was increasingly valued and heeded, both at national and international levels, on issues such as freedom of expression, translation, the problems faced by women writers and the very simple question of how to bring writers together across cultures and languages. Our campaigns against the censorship, persecution, imprisonment and murder of writers also never flagged, becoming increasingly sophisticated.

The Rushdie affair

During the 1980s and 1990s, PEN’s work on behalf of persecuted and imprisoned writers became well known by the international community, amongst writers and governments alike. In 1989 Salman Rushdie, winner of the Booker Prize eight years earlier, received more international attention then he had bargained for with the publication of his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses. He was forced into hiding after Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a religious edict: the notorious fatwa (the word entered common usage in the West thereafter). The fatwa called for the author’s death for, supposedly, having insulted Islam in the novel. Rushdie’s ordeal is now part of literary history; he quickly became a symbol at the time, as a writer persecuted for his words. PEN played a key role in the global campaign that called for the withdrawal of the fatwa, and supported publishers of the book worldwide. Rushdie is, to this day, an active member of PEN International, and the former president of the PEN American Centre.

Ken Saro-Wiwa: a hero silenced

In 1995, the focus returned to Nigeria. PEN had, during the early 1990s, followed the case of the novelist, screenwriter and human-rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had first been arrested in 1992 for campaigning on behalf of the Ogoni people of the Niger Delta. The Ogoni were demanding greater autonomy, and Saro-Wiwa urged multinational petroleum corporations such as Royal Dutch Shell to take responsibility for clearing up the environmental damage to Ogoni lands caused by oil extraction.

He was released after a few months, but was detained again in January 1993 for one month following a peaceful protest that had been violently suppressed by Nigerian security forces. In May 1994, four Ogoni chiefs were killed by a mob of militant Ogoni activists. Saro-Wiwa, who had earlier been prevented from attending a meeting with these chiefs, was arrested again along with fourteen leaders of the Ogoni rights movement.

Charged with inciting the murders, he was convicted despite claims by many observers that the trial was rigged. On 10 November 1995, after an extensive international campaign led by PEN Centres around the world, Saro-Wiwa was executed. An international outcry ensued, and in 1996 a lawsuit was filed against Shell alleging the corporation’s complicity in human-rights abuses in Nigeria, including the killing of Saro-Wiwa. (In 2009 Shell agreed to pay a settlement of US $15.5 million, though the company continued to claim it was not guilty of the charge.)

Two assassinations

In October 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, a high-profile Russian journalist from the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta who had received death threats for her reporting on the war in Chechnya, was found murdered in the lift of her Moscow apartment building. PEN International has since been at the forefront of efforts to bring her murderer(s) to account.

Three months later, in January 2007, the Armenian-Turkish writer and newspaper editor Hrant Dink was fatally shot in Istanbul. Dink had been charged under Article 301 of Turkey’s Penal Code for ‘insulting Turkishness’ through his writings, which challenged the Turkish government’s refusal to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Following his murder, PEN International helped support Dink’s family, and demanded a full and open investigation into his death. (A young Turkish ultra-nationalist was eventually sentenced as the assassin, and several other men were implicated and tried as well.)

PEN International is now active in over 100 countries, and still echoes Dawson-Scott’s and Galsworthy’s original principles advocating freedom of expression, peace and friendship. Those writers’ voices, and those of the many others who joined them over the past 90 years of our existence, are still very much with us. Without them, PEN International could not have become the strong, vibrant, active movement it is today.

http://www.pen-international.org/our-history/#sthash.FWrCmbfu.dpuf

国际出版商协会和国际笔会严重关注四位香港出版从业者失踪

国际出版商协会和国际笔会严重关注四位香港出版从业者失踪

中国动态:严重关注四位香港出版从业者失踪

国际出版商协会和国际笔会对有关香港一家以出版发行批评中国当局而著称的出版社及书店的四位相关人士失踪的报道感到震惊。巨流传媒的瑞典籍东主桂民海,以及总经理吕波、书店经理林荣基、和工作人员张志平都据报失踪。关于他们已被中国当局拘捕的担忧越来越强烈。

国际笔会主席詹妮弗·克莱门特(Jennifer Clement)说:“国际笔会深切关注有关四名出版从业者在中国失踪的最新报道。如果证实他们确实被拘捕,这将是对该国日益收紧的言论自由的又一打击。中国当局应调查报道中的这些失踪案件并立即澄清情况。”

国际出版商协会主席理查德·查金(Richard Charkin)说:“我们严重关切这些人的安全。如果他们确实是被逮捕了,那么这是中国政府开展行动试图在香 港压制异议的又一个案例。国际出版商协会呼吁中国政府立即公布这四个人是否确实被拘留,若然罪名是什么。无论何种情况,我们要求中国 政府尽一切努力来协助寻找这些出版从业者,并允许他们安全返回。”

有关信息,请联系Sahar Halaimzai:+44 (0)20 7405 0338 : [email protected]

(独立中文笔会狱中作家委员会翻译)